Growing up, I always wondered why I was not supposed to rest my elbows on the dinner table. Other seemingly pointless mealtime expectations perplexed me as well: waiting for others before starting in; draping a napkin across my lap; requesting that someone pass a dish (rather than reaching for it); and, when taking my leave, formally asking to be excused. Where did these rules come from? It turns out that Americans did not always embrace these standards—at least not until the Victorians got a hold of dinner in the mid-nineteenth century and re-invented it, determining, among other things, precisely where (and where not) it was proper to place one’s elbow.

For much of early American history, etiquette at the dinner table was minimal, and eating was notoriously rustic—today’s slurper would have been right at home! Fingers and bread sops often substituted for utensils, diners shared trenchers and drinking vessels, and no one would have lifted an eyebrow if a dinner-mate opened his mouth to speak while still chewing. Few rules dictated which subjects were proper to discuss at the dinner table and which unfit, perhaps because meals were not particularly social and conversation could be sparse. Eaters preferred to focus on the business at hand: refueling work-weary bodies for another round of arduous chores.

With the Industrial Revolution, everything changed. Prosperity and the emergence of a middle class transformed dinner into a time when families celebrated the newfound economic progress that enabled them to consume fancier goods. China sets, matching chairs and tables, a sideboard for serving, and a special room set aside for dining—all became markers of status, as did the more refined, French-inspired dishes of the era, presented in a sequence of courses usually by one or two household servants. But merely having these status markers was not enough; you had to know how to use them. Etiquette manuals flourished, instructing the mystified as to the proper setting of tables, sequence of courses, management of servants, topics of mealtime conversation and use of utensils. The extent to which a family practiced the new dinnertime gentility was the extent to which they had become middle class.

For children, the dining room functioned as a school of manners. Here, little ones learned to sip soup from the side of the spoon (not the end), to avoid all mention of bodily references during conversation (even the word “stomach” was considered vulgar), and to refrain from yawning or leaning a chair back on end. Such rules taught children self-discipline and restraint, important Victorian values that parents believed would translate from the dinner table to other areas of life. These rules also trained children for interacting with the larger world beyond the home. With the growth of cities, more and more people inhabited a world of strangers. Etiquette served as a tool for navigating that world, and the dinner table is where etiquette was incubated.

For children, the dining room functioned as a school of manners. Here, little ones learned to sip soup from the side of the spoon (not the end), to avoid all mention of bodily references during conversation (even the word “stomach” was considered vulgar), and to refrain from yawning or leaning a chair back on end. Such rules taught children self-discipline and restraint, important Victorian values that parents believed would translate from the dinner table to other areas of life. These rules also trained children for interacting with the larger world beyond the home. With the growth of cities, more and more people inhabited a world of strangers. Etiquette served as a tool for navigating that world, and the dinner table is where etiquette was incubated.

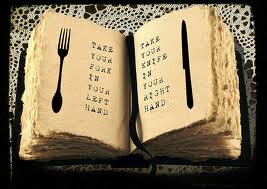

Exercising proper etiquette at the family dinner was also a rehearsal for the all-important formal dinner party. Here, men and women expanded their social circles, reinforced class standing, and networked professionally. To wield a fork and knife properly was essential, along with mastering countless other details of dinner-party protocol, and failure to do so not only carried the possibility of embarrassment but could expose the diner as a fraud—an overly ambitious laborer masquerading as a member of the middle class or a country bumpkin posing as an urban sophisticate. In light of these consequences, it is hardly surprising that parents, who wanted their children to become successful adults, took the instruction of table manners so seriously.

For some time now, American dinner-table manners have been in decline. A casual approach to eating, including relying on one’s hands, is not only standard, but encouraged by countless everyday foods, from sandwiches and candy bars to foil-wrapped burritos and packaged snacks. To approach a hot dog with knife and fork would be as pretentious as wearing white gloves to dinner (another Victorian standard). We’ve come full circle, our lax approach to mealtime mirroring the casual approach of the colonists. But Victorian norms have deep roots in our culture, and they still inform the way we eat—or at least the way we think we should eat.

For some time now, American dinner-table manners have been in decline. A casual approach to eating, including relying on one’s hands, is not only standard, but encouraged by countless everyday foods, from sandwiches and candy bars to foil-wrapped burritos and packaged snacks. To approach a hot dog with knife and fork would be as pretentious as wearing white gloves to dinner (another Victorian standard). We’ve come full circle, our lax approach to mealtime mirroring the casual approach of the colonists. But Victorian norms have deep roots in our culture, and they still inform the way we eat—or at least the way we think we should eat.

So next time you chide junior for reaching across the table, leaning his chair back on two feet, interrupting the dinnertime conversation with a loud, unwelcome burp, you can thank (or blame) the Victorians, who strictly forbade resting elbows on the table and prescribed many of the other dinnertime civilities that remain in play today.

Abigail Carroll’s new book, Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal, explores how our eating habits reveal as much about our society as the food on our plates, and how our national identity is written in the eating schedules we follow and the customs we observe at the table and on the go. She is a food historian, a former teacher in the Gastronomy Program at Boston University, and the author of articles in a variety of publications, including The New York Times. She holds a PhD in American Studies from Boston University and makes her home in Vermont.