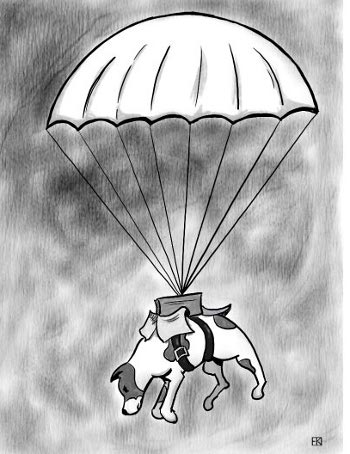

This will be the first Thanksgiving without my father at the table. I will certainly think of him as I eat the sweet potato pudding that he loved and declared “the best he ever had,” year after year. But, more than the food, I will recall the stories he told around the table. Some were about great daring and resilience, like the time his submarine was torpedoed by Germans in the Mississippi River and he had to swim to shore, wondering if he would ever get out of America to fight the war. Some stories were about his hijinks, like the time he outfitted his army mutt with a parachute and pushed him out of a plane, an event that was captured on the front pages of the military newspaper, Stars and Stripes. A few years ago, when he was 90, my family and I recorded several hours of his storytelling, and this Thanksgiving I look forward to rereading the transcriptions of those stories. His stories bring him to life. When my sons and nephews retell his stories, which they do throughout the year, I know he will live on even after I do.

We learn about our families from the stories that we tell, and our brains are wired to understand each other through stories. There are many examples of how are brains are sponges for narrative: We can remember facts more accurately if we encounter them in a story rather than a list. We tend to rate legal arguments as more convincing when they are constructed as narratives rather than as legal precedent. Kids who know stories about their family history have higher self-esteem and well-being.

One puzzling aspect of family stories is how in a given family, thousands of stories are told, and yet only a small subset of those get retold. Consider a family of four and their story-generating capability. If each member tells one story a night for 18 years, they will have come up with 18,000 stories, yet only a fraction of those make up the family’s portfolio of favorite stories. The stories told over and over again usually convey important beliefs that a family holds dear — like the idea that a bad piece of luck can turn out to be good luck, or how a surprising random event can make life take off in an unexpected direction, or the importance of never giving up.

Sometimes, we need great questions to tell interesting stories. Some wonderful questions are available at Story Corps, the national oral history project that invites Americans to record, share and preserve stories of their lives. This project honors the importance of everyone’s life story.

If you want to enliven your Thanksgiving table conversation, you might want to try out some examples of questions from the Story Corps website.

- What has been the happiest moment of your life?

- Who has been the biggest influence on your life? What lessons did that person teach you?

Or you may want to ask your parents:

- How did you choose my name?

- What was I like as a baby? As a young child?

- Do you remember any of the songs you used to sing me?

The website has questions to ask friends, parents and grandparents. It also includes questions about a wide range of topics like religion, love, school, work, serious illness, and war.

So many of our memories of Thanksgiving are contained in the sensual details of the smell, tastes, and look of the foods. Our stories about the foods may be just as delicious, and memorable, as the sweet potato pudding.